Transcendent values

Transcendent values are values which are not captured by any formal description.

The study of DAOs requires an understanding of general human groups. What keeps a group stable and coherent? Centralized organizations can rely on more efficient power structures which protect their membership and maintain their coherence. Open decentralized organizations can only exist if their members share common purpose. This requires a common set of values that are specific enough to direct the group toward a common goal and identify and prevent behaviors which threaten that purpose. The Transcendent Values Thesis explains why these values must not be too specific if a DAO is to succeed.

Different DAOs, with different organizational goals, will have different transcendent values and also differ in the importance with which they are ascribed. Thus transcendent values can be distinguished from universal values.

This page explores game theory arguments for the Transcendent Values Thesis and explains how DGF is designed to give DAOs the governance tools to promote and police their values.

Background

The most important attribute for a DAO’s long term stability is its values. Values are what determine a DAO's membership, which are far more affecting in a decentralized group than a centralized group. A centralized group’s members are less independent and more subject to the dictates of leadership, due to the hierarchy of control. A decentralized group, especially one which is open (meaning no barriers to entry or exit), must embody the values of its membership, or else its members will quit and the group will collapse.

The values of a group are its goals. The goals of a group tell you where it’s going. A decentralized group is necessarily less nimble and more plodding than a centralized group. A centralized group can change course as soon as its leader decides. A decentralized group must convince a majority of its members before any major changes are made. And that majority must be near unanimity, lest the group lose members through conflict, which weakens it significantly because of the network effect. Therefore by understanding the values of a DAO we have a strong chance to predict its behavior, farther into the future than the centralized corporate analogs.

There is an inherent tension in the idea of a DAO. On one hand, a DAO is necessarily decentralized. A DAO must be decentralized in the ownership or control of the power of the group. This allows it to incorporate diverse perspectives and talent and knowledge, to incorporate information at the edge. On the other hand, to remain coherent—to stay organized—these diverse individuals must be united in a common purpose, a common goal. Members must share a common set of values. A DAO's values are not diverse. The members must agree on a set of acceptable behaviors and standards. A DAO's protocols must be centralized.

The protocols around which the DAO is centralized will be extremely explicit, rigorous, formal. In fact, these rules are encoded in programmed smart contracts. The regulation and execution of the protocols are automated in implacable programs. Code is law.

The reason these protocols must be so crystalized in a primary DAO is that justice for a group of pseudonymous participants from diverse backgrounds requires extreme objectivity. Under the circumstance that we don't have intimate knowledge of members' backgrounds, fairness requires that everyone's actions must be judged equally regardless of their idiosyncratic motivations.

The primary[1] problem with making the protocols perfectly rigorous is the inevitable potential to game the rules. Experience with various repeated games from game theory, which culminate in the Folk Theorems, suggests that whenever a group makes formal rules for acceptable behavior, an adversary can follow those rules to the letter and profit at the expense of the majority. When rules are rigid, players will push the limits of those rules. Competition within the organization then saps the power it gains from cooperation. Therefore the letter of the law, though necessary, is not the ideal protocol to follow. Following the spirit of the law is more important for maintaining long-term cooperation in a primary DAO.

Thus DAO governance cannot merely consist of a static set of programmed rules. There must be an evolutionary structure of governance that allows review of past behaviors, to reward behaviors which help the DAO and punish behaviors which harm the DAO. The very existence of the ability to reward and punish serves to motivate healthy, collaborative behavior and prevent harm to the DAO.

"Harm to the DAO" is often a subjective judgement which requires referencing the values of the DAO. To know whether something constitutes harm requires us to know what is bad, which requires us to know what is good, which requires us to know what we value. Thus a DAO must express their values so its members can achieve harmony. However, if they formally express their values, that is equivalent to explicitly setting the rules, which again promotes competition and allows adversaries to game the system.

Therefore, to maintain long-term stability, harmony, and collaboration, a DAO needs to have a common set of informal values, values which are not capable of being made rigorously explicit, values which transcend any formal rules. This is why we make reference to the philosophical concept of transcendence.

There are many examples of transcendent values used by different groups throughout history. The Neoplatonists singled out Goodness, Beauty, & Truth, which informed early Christian thinking. Stoics valued Wisdom, Courage, Temperance, and Justice, similar to the Islamic values of Submission, Charity, Temperance, and Justice, which are values shared by many clan-based societies throughout the world. Buddhists identify the Threefold Training of higher virtue, mind, and wisdom. In nearly every religion there is a fundamental assumption that the highest representation of the good, or God, transcends the formal knowledge of human categories of understanding.

Transcendent Values Thesis

No formal rules for a group's membership and behavior can be made which prevents adversaries from violating the intent of the framers, corruptly profiting at the expense of the majority, while following the rules.

Therefore, the ultimate rules that govern a group should not be explicitly stated. The highest rules should be vague, but pointing as directly as possible to some common values that transcend formal description.

More simply, the Transcendent Values Thesis[2] is: For the long-term stability of an organization, the spirit of the law is more important than the letter of the law.

Game theory evidence

In any slightly complicated repeated game, like Repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma in real life, no static set of formal rules exist which guarantee everyone will get a fair reward. No matter the strategy of the rule framers, there is another strategy that an adversary can discover, likely more complicated, which will gain profit for them at the expense of the group.

The Folk Theorems of game theory give motivation for such claims. In each game that is as complicated as the Repeated Prisoner's Dilemma, we find an infinitude of strategies that give Nash Equilibria. And there are infinitely many variations on the Prisoner's Dilemma that give sub-game perfect strategies, including assumptions such as

- whether the players can communicate

- whether policing deviations from the rules is costly to the group

- whether information about a player’s history or reputation is available to the group

- stochastic variations

- “trembling hand”

- imperfect reporting of results

- imperfect memory of the past

However, any real-life situation is infinitely more complex than any mathematically formalized game. And the motivations of each player ultimately transcend any formalization. Desires change as soon as a rule does. So we expect there to be infinitely many successful strategies for any real-life contest. No static set of rules will be able to prevent a player from exploiting those rules for their corrupt profit at the expense of the group.

What is a thesis?

The Transcendent Values Thesis is a thesis and not a theory or theorem, because it is not a logical statement; it cannot be formally proven or disproven. A thesis, in mathematics or philosophy, is a claim that transcends the ability of your current logical system to describe formally.

The reason the Transcendent Values Thesis is a thesis, is that it is pointing toward the situation that people playing a complicated game are capable of having desires and intentions that violate the expectations of the framers of the rules of the game. So the framers' intentions can always be subverted. The idea of fairness in a game is dependent on the framers' intentions, which precede and transcend the rules.

Consequences

Blockchain architecture

Consensus mechanisms for block production, such as Proof of Stake (PoS), are directly affected by the Transcendent Values Thesis. A PoS algorithm relies on a decentralized network of nodes to follow protocols and check that the other nodes are also following those protocols for constructing new blocks of data.

However, there is always leeway in how a node produces a new block, which gives opportunities for corruption. For instance, the consensus mechanism exists to create a canonical view of the network, periodically. The issue is that there is no natural canonical view. Each node has a different perspective, for instance, on the issue of the chronology of messages in the gossip network. How does the network decide which transaction was uploaded first when two messages are sent to two different nodes within the latency period of communication between those nodes. Therefore, one of the functions of block production is to artificially create a canonical view of the gossip network, at successive periods in time.

Censorship is also a major difficulty, where a block producer might choose to ignore certain messages and not include certain transactions in their new block. As a simple example, a block producer could arbitrage their network power by purchasing a stock for a lower price than was bid by a user that the block producer chooses to censor. Then the block producer can sell the stock to the bidder for the higher price, making a guaranteed personal profit at the expense of the market.

In this situation, block production entails complicated rules for a repeated game. The Transcendent Values Thesis claims it is not possible to create an algorithm that will prevent every possible approach to subverting the intentions of the algorithm's designers to prevent corrupt behavior. Therefore there is an inevitable arms race between the architects who must make ever more complicated algorithms, against potential or actual corruptors who will find ways to profit unfairly by gaming the system.

The best way to escape this arms race is by giving the potential corruptors incentives to improve the algorithm rather than exploit it. For this, the blockchain platform needs a system of governance sophisticated enough to effectively reward such behavior and punish exploitation. This motivates DGF:

DAO design

The Transcendent Values Thesis (TVS) motivates the creation of DGF as informs its design. It requires us to create a system of governance for any slightly sophisticated DAO, assuming we cannot engineer some perfect protocols that can anticipate all future market behaviors. TVS requires this system of governance to be fundamentally flexible, incorporating eternal evolution as a basic assumption. It requires review as a basic mechanism, assuming whatever protocols have been instantiated in the past will be insufficient to guarantee uniformly healthy and helpful contributions throughout time. Therefore we instantiate judicial governance mechanisms for reviewing past actions and legislative governance mechanisms for reviewing the very protocols for reviewing past actions.

Judicial protocols such as references, which reward posts that improve the platform or punish participation that later is deemed to be harmful to the platform, can motivate potential corruptors to instead create improved policing mechanisms. At the very least, when the incentives are insufficient to prevent such Byzantine behavior, the judicial reference mechanisms can correct the consequences of the corrupt behavior, stabilizing the function of the platform.

Religion

The Transcendental Values Thesis gives academic justification for the necessity of the existence of religions, which are universal throughout human groups. For long-term stability and integrity, groups need to share common values which are beyond the ability of rigorous symbols to formally capture with logical strictures for behavior.

The thesis also explains the failure of any formal religion to be universal and eternal. Religions entail formal protocols for behavior, i.e., ceremonies and rituals. Their centralized protocols lead to hierarchies of power which are then gamed, corrupting and destabilizing the group. Therefore religions inevitably collapse under such destabilizing internal competition.

Therefore the protocols of a long-term stable religion require transcendent principles--principles which transcend any formal description. The experience of transcendent values are of a "know-it-when-you-see-it" nature. We cannot define absolute good, but we recognize what is good and bad when we are honest and observant.

Primitive values

There are some basic principles which help identify an organization's values. Whether a group's values are stated or unstated, we can analyze their value system by evaluating the group's behavior by considering some primitive notions.

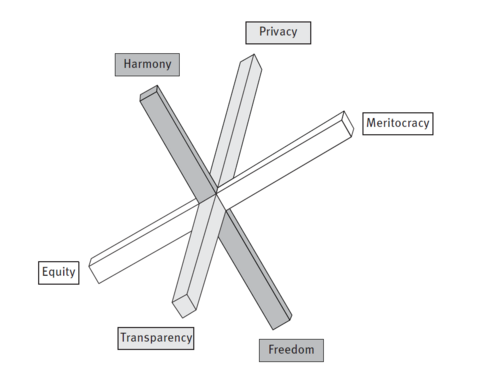

Analyzing any structure of any system or organization is a matter of identifying its primary components and their relationships. The five primitive notions[3] we use to analyze a DAO's values are 1. the individual versus 2. the group, and the a) transmission, b) processing, and c) storage of information. Then, in designing or evaluating a DAO, the most basic categories of its goals, its primitive values, emerge as the following: freedom versus governance, privacy versus transparency, and personal ownership versus the commons. The analytical framework we use here is the most common triad taken from information theory: the study of information is broken down into the categories of information transmission, information processing, and information storage. In analyzing an organization, the primary concern is between the individual and the group. So the information theory triad is split into six concepts:

- DAO information transmission

- individual: information transmission is personal freedom

- group: information transmission is governance

- DAO information processing

- individual: information processing is personal privacy

- group: information processing is bureaucratic transparency

- DAO information storage

- individual: information storage is private holdings, i.e., personal ownership of DAO power tokens (REP)

- group information storage is the commons held in social equity[4], e.g., the history of DAO contributions, its IP knowledge base including the collection of smart contracts, and its collective reputation which must be protected from corrupting individual exploitation.

|

Information Transmission | Information Processing | Information Storage | ||||

| Individual | freedom | privacy | meritocracy | ||||

| Group | governance | transparency | commons |

It is fundamental that these basic ideas are in polar relationship to each other.

There is an inherent tension between group power and individual power. Individual behavior as freedom, privacy, and personal ownership is not a call to maximize those expressions without constraint. For example if an individual maximally expresses their freedom, then group governance is threatened. If an individual does whatever they wish, if they refuse to stifle whatever personal urge arises, it threatens group cohesion.

Individuals’ behaviors must be constrained to belong to a group. And the group’s power of suppression must also be limited. Maximizing the group’s expression of governance, transparency, and social equity without constraint is not sustainable without crushing its individual members' power and freedom. If the group crushes every expression of individual freedom, then its members are weakened, which ultimately diminishes the group.

In order to maximize all these values effectively, the three pairs of polar opposites must be well connected, in healthy tension. When individuals voluntarily constrain the expression of their freedom to improve group collaboration, voluntarily share their personal information with the group, and voluntarily give up some property to the commons, then group function is improved. Similarly, inasmuch as the group can limit their overt control over the individual by minimizing governmental action, then their membership becomes individually more powerful. Thereby the group becomes more successful. To state this more plainly, both the individuals and the group should become as powerful as they are able, then restrain themselves in their use of that power. Such contradictions can only be sustained with a culture that remains conscious of those necessities for long term success.

Each DAO’s values can be evaluated by how they perform in these six categories, which can be contrasted with the internal rhetoric and external propaganda the DAO produces. In general, a DAO’s health and outlook can be measured by how it maximizes the expression all of these polar opposite values. In general, contemporary DAO leadership has wisely favored the group designing protections for individual values, inasmuch as they have formalized their constitutional values. However, that has had the effect of lopsidedly ignoring the development of a culture which encourages the individual virtues of contributing to the group selflessly. This necessarily weakens each DAO which purely rewards selfishness, as this can only last as long as founder zeal can sustain their naïve idealism. A focus on group-generated individual reputation can remedy such unhealthy imbalances.

Each of these six categories generate jargon particular to these primitive notions in the literature on DAOs, such as: open network, open source, smart contract, “code is law”, crypto, and pseudonymity.

- Open network

- global (transnational legal implications)

- internet communication

- freedom of entry and exit for anyone willing to follow the established protocols

- Code is law

- instant algorithmic legal execution through smart contracts, which allow theoretically infinitely complicated business logic thanks to the Turing completeness of the blockchain’s bytecode (modulated by the severe practical limits of actual network speed)

- Pseudonymity

- the same asymmetric encryption (public-key cryptography and ZK-proofs) that allows us to put our banking information online allows us to buy and sell bitcoin without fear of hackers stealing our passwords

- Open source

- Decentralization requires all protocols to be available to exactly the number of people that defines how decentralized the network is. The number of people who have access to the code that governs the blockchain determines the level of decentralization. If it’s not centralized then everyone in the network has equal access to power, so everyone in the network needs equal access to be able to audit the functioning of the blockchain.

- Bureaucratic transparency is baked in to a well-functioning blockchain. However, practical measure of decentralization is severely limited in this case, since expertise is limited. There are far fewer members who have a solid conception of the full technical function of the blockchain than those who use it.

The individual vs group division is an analysis of our subject into two primitives. We can’t define the ideas of single or multiple by appealing to any more basic notions. These primitive notions are essential to understanding the functioning of a DAO at every level. For example, the concepts of centralization and decentralization rely on the primitive analysis into individual and group. Every quality can be analyzed at every level by determining where the subject is on the spectrum between centralization and decentralization, between individual and group, between single and multiple.

For instance, an ideal DAO will be decentralized in the sense that all members have equal potential to gain power in the group. An ideal DAO is an ideal democracy. But every DAO (and democracy) needs to be extremely centralized on another level—protocol centralization. This means every DAO needs to have a single, uniform set of rules (protocols, laws) that the members follow, in order to remain organized.

All qualities will be expressed as more concentrated (individual) or more spread out (group), i.e., as more centralized or more decentralized. Besides protocol centralization and power decentralization, it is also useful to analyze location, member talent, and transcendent values, for example, to determine how coherently or variegated these qualities are expressed in a DAO.

Unity emerges from multiplicity, and multiplicity emerges from individuals. Unity is the linking of multiple individuals—each individual is a united collection of multiple things at a lower level. Each group is a collection of individuals, but not all collections of individuals is a group. A group is a collection of individuals with a common goal, i.e., shared values. Once they have shared values, then their ways of doing things, i.e., their protocols, converge.

The group often starts with different, even incompatible protocols. Each individual in a group follows their own personally invented protocols The group at that stage is protocol decentralized, i.e., disorganized. With enough time, with shared goals and an intent to collaborate, a group can achieve protocol centralization. The group then becomes an organization, meaning it is organized. In the DAO acronym, the D means power decentralization, which comes first, while the O means organization which is protocol centralization. People either compete or collaborate, but to remain a coherent group, eventually a single united group protocol must emerge which all individuals in the group can accept and follow predictably. For this to happen all of the distinct individuals' protocols must change enough to become compatible, allowing them to link, forming a superset of group protocols.

Practical instantiations

DGF transcendent values

Main page: DGF transcendent values

The DGF project is devoted to creating the tools necessary to foster healthy and effective DAOs. The values of DGF are decentralized collaboration; decentralized creation, dissemination, and control of information; and the decentralized ownership of assets. This means we value

- Decentralized organization

- Individual power and freedom

- Group harmony

- Decentralized information

- Individual privacy

- Group transparency

- Open decentralized ownership

- Equity control of essentials

- Meritocratic competition for inessentials

SDF transcendent values

Main page: SDF transcendent values

The transcendent values of the SDF project are to

- Seek Truth.

- Share Knowledge.

- Govern Wisely.

See Also

Notes & references

- ↑ A secondary problem with making the letter of the law the ultimate dictate of control is that it necessarily ignores the motivations of the actor, which are crucial for determining any fitting reward or punishment. A tertiary problem is that it ignores the background of the individual in the explanation of their motivations.

- ↑ Craig Calcaterra, "The Transcendent Values Thesis for DAOs", in Blockchain and Society Handbook, De Gruyter, 2025.

- ↑ A primitive notion is an ultimately basic idea in a system. Primitive notions are used to build up all the other more complex ideas in the system. Primitive notions are the bricks with which we build our mental cathedrals. They are the starting point—the concepts that cannot be defined in terms of more basic concepts. As such, we cannot give a primitive notion a formal definition. Instead, we can only give colloquial descriptions of how we think of them, intuitively. However, once we accept these primitive notions, then all the more complex constructions can be formally and rigorously specified. For example in computer science, a primitive is the most basic object that can be used in a programming language—often a computer science primitive is a logical object associated with a circuit, such as the IF THEN conditional. The idea of a primitive comes from a primitive notion in mathematics or philosophy which is a concept that is so basic that it cannot be defined in terms of any simpler ideas, but is used to define more complex ideas. Examples in geometry are Euclid's axioms, postulates, and first definitions, such as point, line, angle, and the notion of properties of equality. Examples from set theory relevant to our discussion include the notion of a set itself, the notion of an individual object, and the notions of inclusion and exclusion. Since a primitive notion is not explicitly defined, it is therefore defined implicitly, through practice. The understanding of precisely what a primitive notion means can only become progressively clearer as it is given progressively more contextual background, as the primitive notion is used in more applications. The entire field of study that is built on the primitive notions is automatically recontextualized with each new application of the theory.

- ↑ There is an unfortunate terminological ambiguity between economics and sociology. Equity in finance means differentiated individual partial ownership of a company, such as stock holdings. Equity in sociology means the precise opposite. In sociology, equity is the concept of sharing power or goods in a group, which are referred to as the commons, where the distribution is executed according to need. Both concepts are fundamentally important when analyzing DAOs.