DAO: Difference between revisions

(Creating DAO stub; adding Ladd's primitives for the creation of a DAO) |

(Dumped my article's intro into the page. Will need to be completely overhauled) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

A decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) is a ?? | A DAO is the fundamental unit of consideration in the [[DAO Governance Framework project|DGF project]]. A [[wikipedia:Decentralized_autonomous_organization|DAO]] is a decentralized autonomous organization. | ||

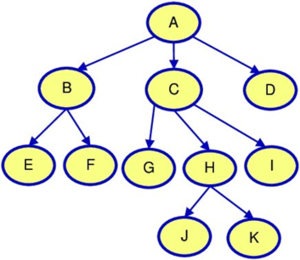

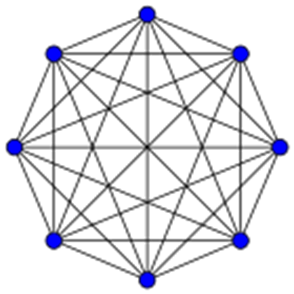

Decentralization is the opposite of centralization. A DAO's governance structure is not centralized. An ideal centralized organization has a completed pyramidal-hierarchical power structure with a single ruler on top (Figure 1a) which dictates authority, distinguishing those above from those below. Perfect decentralization would be absolutely flat (Figure 1b). Imagine a radical direct democracy, where every decision is made with consensus by the entire membership, without fixed roles of authority. | |||

A DAO being an organization, means it consists of a coherent collection of members. Coherent means its members cooperate toward a common socio-economic goal. | |||

Autonomous means the group rules itself. A DAO is not subject to direct control from outside the group. | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|+ | |||

|[[File:CentralizedHierarchyGraph.png|thumb|Centralized]] | |||

|[[File:DecentralizedGraph.png|thumb|Decentralized]] | |||

|} | |||

Figure 1: Hierarchical vs. flat power | |||

In more practical terms, the typical DAO we consider in the DGF project is best thought of as a decentralized, global corporation that uses the internet and computing technology, to make business transactions and to govern itself. As such, a DAO is a community-driven for-profit cooperative that relies on programming to stay organized. | |||

The term for the technology that enables decentralized organization is [[wikipedia:Peer-to-peer|peer-to-peer technology]]. P2P tech consists primarily of the internet, zero-knowledge proofs (including [[wikipedia:Public-key_cryptography|public-key]] digital signatures), [[wikipedia:Hash_function|hash functions]] (a universal tool for organizing data and error-correcting), and the software architecture of blockchains and distributed hash tables. | |||

There are many types of DAOs proposed, but we will explore the most difficult type to build—a profit-centered, open-source, democratically-governed network which is open to pseudonymous, international members. That’s a lot of terminology, but we will explore each term in detail. Not all DAOs enjoy all these properties. Each of these qualities is an option. Instead of our chosen topic, we could have analyzed the opposite types of DAOs, which are non-profit, local social groups. Some DAOs require their members to reveal their identities with '''KYC''' (know your customer) protocols similar to those used in traditional banking. Sometimes a group may even call themselves a DAO without being particularly concerned with decentralization, contradicting the acronym. However, this analysis will assume all these challenging qualities, which we justify as ideal below. | |||

First, however, let us pause to reflect on the profundity of our task. Throughout human history authentic decentralized for-profit groups have very rarely successfully competed with centralized corporations. The only examples the author is aware of are the Maghribis in the 11<sup>th</sup> century and a few bands of Plains Indians in the Americas, such as the Apache and Comanche. The current Web3 inspired enthusiasts have not yet succeeded in their vision. An authentic for-profit DAO will only be proven successful once a potato makes its way from a farm to a city while relying on the DAO’s smart contracts. That DAO will be particularly successful if all the parties involved are not even aware of the technology that underlies the business transaction—similar to how people currently use Google Maps to help them choose restaurants, while they are unaware of Google’s algorithms aggregating the decentralized information from its users to make helpful recommendations. | |||

The goal of building a DAO is as radical as any technological revolution humanity has experienced. To be thoroughly successful in this task requires decentralizing all of society, because inasmuch as a DAO relies on some other centralized institution, that becomes a bottleneck which concentrates control over the DAO, making it ''de facto'' controlled by some centralized decision maker. The degree to which any component can be decentralized is limited by how decentralized its environment is. Therefore, before the first true DAO is born, all of our government, all the businesses the DAO relies on, all of our civic and social institutions need to be revitalized to adapt to these new technological powers. Otherwise, at the very least, decentralized analogs of all these institutions must be created, to support this radical new type of democracy. | |||

This overhaul is limited by our imaginations. We live in societies that have been dominated by centralized institutions, arguably for all of recorded history. Our understanding of decentralization derives largely from our experience with representative democracies, whose decentralization is limited to periodic votes for abdicating personal power to delegates in the government. DAOs are fundamentally different. A DAO is profoundly decentralized, since all members are capable of exerting direct control on the future of the group, via P2P technology, yet no member can assume unilateral power over any other member. | |||

To envision the type of decentralized societies that are emerging, we can turn to history. Until the industrial revolution, the primary narrative in the story of humanity was the conflict between centralized and decentralized societies. Sedentary agriculture-based civilization versus herding nomads. Different inventions through the ages favored different sides in this conflict. The invention of the stirrup favored decentralized nomads, which led to Genghis Khan’s army razing much of the centralized world. The invention of the steam engine favored centralized societies, leading to the near-complete destruction of most nomadic cultures, due to the effects of statically-located factories producing great quantities of new inventions that favored sedentary economies, such as barbed wire. | |||

Today, however, the inventions of the internet and personal computing enable peer-to-peer technology, which favors decentralized organization. New nomadic cultures are forming, as business can be done between individuals across national lines through virtual travel, enabled by video conferencing and distributed databases. | |||

How can we use these new technologies to architect new types of organization to match our new powers? | |||

== 1.1 Ideal DAO qualities == | |||

How does a decentralized institution emerge? How is a DAO built? What primary qualities must it have? The ideal qualities of a DAO are that it is open to pseudonymous, international members who democratically control transparent business transactions with open-source, secure governing protocols, using reputation as the measure of governmental power. Such a DAO is called a '''primary DAO'''. In the context of DAO building, let us carefully explain and justify all these terms: | |||

1. Openness | |||

2. Pseudonymity | |||

3. Transparency | |||

4. Open Source | |||

5. Security | |||

6. Weighted Democracy | |||

7. Reputation Incentive | |||

Before defining these terms, it is crucial to recognize they are ideals. As such they are never expressed with perfect purity in real world organizations. Actual DAOs exist on a spectrum of these qualities. | |||

A DAO being '''open''' means its rules for accepting new membership is unrestrictive—everyone in the world has equal access to join, an equal opportunity to gain power, and an equal freedom to leave (while taking much of their personally accumulated value with them). It is preferable that a DAO adopt these properties of openness for two primary reasons. | |||

First, an open network encourages greater growth, and the '''network effect''' shows a decentralized group grows in power faster than a centralized organization as its membership increases. To see this, notice how members don’t merely have connections, they have individual connections. Connections grow quadratically with membership. A group of members also has an exponential number of potential subgroups. Each subgroup of size has different role assignments. Etc. As a group grows, there is more talent and more knowledge with quadratically more connections and exponentially more arrangements to foster more powerful collaboration. An open DAO leverages the available energy of the population more effectively than a closed DAO. This network effect is a major reason that decentralized organizations can be superior to centralized organization, because a rigid hierarchy is limited to a single power structure for organizing its members to achieve a task. | |||

The second major reason openness is ideal is that it serves the social good. It is a matter of basic justice that all people in a society are given equal opportunity to participate in all of its institutions. People prefer not to participate in a group that does not serve their values, especially one that limits their opportunities to gain power in the group. More importantly, they should not be forced to participate. | |||

However, openness is a major security risk that needs to be continually addressed. Equal opportunity to participate is essential, but the types of participation that are beneficial to the group are naturally limited. Members who behave poorly must lose some of their power in the group, lest the group be destroyed by selfish behavior which virally spreads until the group becomes completely disorganized. Corruption must be limited or it will multiply until it destroys the group.[1] Therefore, to maintain openness, a DAO needs strong, automated, executive governance. | |||

'''Pseudonymity''' means a member may participate with one or more fabricated identities[2]. An example is when you invent a fake username on an internet message board. It is preferable that a DAO allow members to join pseudonymously for three major reasons. | |||

First, privacy is essential for protecting the individual. Since all transactions must be openly monitored by anyone in the decentralized network, every behavior in the DAO is recorded eternally and broadcast globally. In addition to the fear of social censure decades after any particular behavior, keeping a record of a citizen’s minute behaviors is a powerful tool which encourages governmental repression of its citizens at all levels. Pseudonymity is the closest one can achieve to anonymity on a transparent platform that remembers transactions and gives its members power and rewards. | |||

Second, this protection of individuals’ privacy encourages more members to join. Again, the network effect gives larger groups more than a quadratic advantage in the many sub-dimensions of power, capital, and knowledge. | |||

Finally, pseudonymity encourages a culture of forgiveness. Mistakes are inevitable. Forgiveness is essential to promote the network effect. Regardless of the intention behind the mistake, if it is possible to forgive members without eroding group cohesion, a culture supporting redemption should be promoted. Though it should be recognized that, unfortunately, pseudonymity makes apologies unnecessary, since they can simply quit and start fresh with a new identity. Conscious of this fact, a culture of redemption can still be encouraged if the DAO sets up protocols giving greater power to someone who has atoned for a mistake than to new members. | |||

However, pseudonymity is a major security threat in an open DAO as it opens the group to sock puppet attacks, which we discuss below. | |||

'''Transparency''' means the functions of the DAO are publicly observable. In particular, the types of technology used, the specifications for the design of the technology, the membership, the actual rate and quantity of computations or transactions, the protocols for acceptable transactions, protocols for policing transactions, the protocols for changing protocols, and even the culture of decision making, can all be made more or less transparent in any network. Inasmuch as knowledge is limited to certain individuals, when transparency is limited in any way, power becomes centralized among the subpopulation of the DAO which has the knowledge. Thus transparency is correlated with openness and power decentralization in DAOs. However, transparency is a major threat to members’ privacy, which is ameliorated when the DAO supports pseudonymity. | |||

'''Open source''' means, minimally, that the computer code that runs the technology the DAO uses is publicly available knowledge. Similar to transparency, open-source protocols are generally necessary in an open DAO because inasmuch as it is decentralized, all members are more or less equal. No member has privileged information. Without a more powerful leader, everyone in the network needs to be able to monitor everyone else. Everyone needs to have access to the knowledge of the architecture of the system in order to audit its functioning. This is not strictly necessary in a weighted democratic governance system, since certain members can have greater power than others. But inasmuch as such power disparities obtain, the DAO is less decentralized. | |||

'''Maximal open-source''' tech means the legal right to use that technology is given away freely, without claiming any royalties, to anyone else who wishes to use it, for any reason. An example is the Apache license[3], which governs a significant portion of internet technology. The Apache license allows you to adapt their free tech and improve it. Moreover, you can then claim ownership of your improvements and demand royalties. Such maximal open-source protocols are not necessary for any DAO to adopt. However, it is good practice to assume your protocols will be maximally open source when designing a DAO, because the international character of any open DAO makes jurisdictional questions impractical to decide and enforce. Protecting your IP in this environment is better handled by using the first mover advantage, combined with the network effects that make your DAO more powerful than any later imitators. This works best when additionally, a culture of proper referencing evolves to acknowledge and fairly reward improvements from the past. Such meritocracy can promote a more effective collaboration environment than one which stresses competition and secrecy. | |||

'''Security''' is a constant concern in the design of an open-source protocol. Especially when the network is open to pseudonymous members. '''Byzantine''' behavior in a decentralized network, is defined as actions which violate the majority agreed protocols. When there is no dictator ruling your platform, and you accept asynchronous distributed transactions entering from any node, it is impossible to achieve perfect intelligence about the state of the network, since Byzantine nodes can pass false messages in the gossip network. There are several theorems in computer science that govern what is possible when designing a protocol for distributing digital token rewards in a DAO. A famous example is the 66% non-Byzantine limit for the pBFT algorithm. In general, no decentralized system can survive forever in the face of 51% Byzantine actors. Therefore some restrictions to openness are necessary. | |||

Another major security risk to a decentralized platform is a sock puppet attack. '''Sock puppets''' are multiple pseudonymous accounts that a single member creates and controls with separate passwords to hold digital tokens. The purpose of sock puppet accounts is to trick the network into believing the different pseudonymous identities represent multiple people. This eliminates any chance that a DAO without KYC protocols can achieve honest governance under simple one-person-one-vote democracy. Since anyone on the planet has equal opportunity to participate under a fabricated identity, a single actor can create countless sock puppet accounts to overwhelm the voices of honest members. Therefore, any DAO work model or governance design must account for this eventuality. The solution to fighting sock puppet attacks, is a weighted democracy which assign rewards and power based on carefully audited measures of positive contributions to the group. | |||

A '''weighted democracy''' is a governmental structure where the power to decide the protocols for the DAO is determined by vote ('''democracy'''), but the power of each person’s vote may be different ('''weighted'''). This is necessary in an open pseudonymous group, because it eliminates the threat of sock puppet attacks: 100 sock puppet accounts voting with 1 weight each have the same power as a single account voting with 100 weight, since both situations have the same total. | |||

How is this weight of power determined? In most of the original functioning DAOs, power is dictated by ownership of the currency token. In that case plutocracy is the ''de facto'' governmental structure. Little reflection is needed before most new DAO architects reject this design. Instead the common solution is to build their DAO on reputation. | |||

'''Reputation''' is a personal judgement based on your past actions. Business relies on your counterparty’s reputation to predict how they will act during a transaction, to give you the confidence to enter a bargain. The proper attitude for a healthy market environment is to seek to improve and protect your reputation for the long term, not to simply acquire as much money as possible in a single business deal. A secure and reliable system that accounts for meaningful reputation transforms such zero-sum competitive behavior concerned with immediate profits into an environment which motivates future-oriented, sustainable cooperation. When a single game turns into a repeated game, the incentives are transformed. In a system with repeated business, reputation is actually a positive sum quality, since it can be created from nowhere. Whenever two parties behave well and collaborate productively, perhaps sacrificing their own short-term gain on some aspects of the deal, they produce valuable reputation that signals further positive interactions in the future.[4] | |||

How can we foster a culture which respects and values reputation more than money when your DAO allows pseudonymous members to join or leave at will? Properly designing and programming a robust mechanism that is secure against the infinite strategies for gaming any algorithmic reputation system is not a simple task. The remainder of this chapter is devoted to explaining how to capturing the meaning of genuine reputation with digital REP tokens, analyzing the system’s security, and specifying precisely the economic value of a REP token, and detailing important applications. | |||

----[1] '''Corruption''' is defined abstractly in a system as the result of a minority profiting at the greater expense of the majority. Corruption is a type of friction that is inevitable in any system, because the will to profit is essential and the accounting to determine whether a minority’s profit is at the greater expense of the majority is generally not a tractable problem before the fact. | |||

[2] Pseudonym technically means false identity, which has a negative connotation. It would be preferable to have a more neutral term meaning fabricated name, such as technonym, synthenym, artinomen, or fabrinomen, since the identities we are discussing are not necessarily inherently false. However, the term pseudonym is firmly established in the field. | |||

[3] <nowiki>https://www.apache.org/licenses/</nowiki> Retrieved 18/2/2023. | |||

[4] An elaborated argument for the necessity of reputation in business is given in Chapters 4 and 6 in [??Craig Calcaterra and Wulf Kaal, Decentralization, De Gruyter, 2021]. We rely on game theory [?? George J. Mailath and Larry Samuelson, Repeated Games and Reputations: Long-Run Relationships, Oxford University Press, 2006.] and history [??Avner Greif]. | |||

== Fundamental Considerations[edit | edit source] == | == Fundamental Considerations[edit | edit source] == | ||

Revision as of 04:22, 27 February 2023

A DAO is the fundamental unit of consideration in the DGF project. A DAO is a decentralized autonomous organization.

Decentralization is the opposite of centralization. A DAO's governance structure is not centralized. An ideal centralized organization has a completed pyramidal-hierarchical power structure with a single ruler on top (Figure 1a) which dictates authority, distinguishing those above from those below. Perfect decentralization would be absolutely flat (Figure 1b). Imagine a radical direct democracy, where every decision is made with consensus by the entire membership, without fixed roles of authority.

A DAO being an organization, means it consists of a coherent collection of members. Coherent means its members cooperate toward a common socio-economic goal.

Autonomous means the group rules itself. A DAO is not subject to direct control from outside the group.

Figure 1: Hierarchical vs. flat power

In more practical terms, the typical DAO we consider in the DGF project is best thought of as a decentralized, global corporation that uses the internet and computing technology, to make business transactions and to govern itself. As such, a DAO is a community-driven for-profit cooperative that relies on programming to stay organized.

The term for the technology that enables decentralized organization is peer-to-peer technology. P2P tech consists primarily of the internet, zero-knowledge proofs (including public-key digital signatures), hash functions (a universal tool for organizing data and error-correcting), and the software architecture of blockchains and distributed hash tables.

There are many types of DAOs proposed, but we will explore the most difficult type to build—a profit-centered, open-source, democratically-governed network which is open to pseudonymous, international members. That’s a lot of terminology, but we will explore each term in detail. Not all DAOs enjoy all these properties. Each of these qualities is an option. Instead of our chosen topic, we could have analyzed the opposite types of DAOs, which are non-profit, local social groups. Some DAOs require their members to reveal their identities with KYC (know your customer) protocols similar to those used in traditional banking. Sometimes a group may even call themselves a DAO without being particularly concerned with decentralization, contradicting the acronym. However, this analysis will assume all these challenging qualities, which we justify as ideal below.

First, however, let us pause to reflect on the profundity of our task. Throughout human history authentic decentralized for-profit groups have very rarely successfully competed with centralized corporations. The only examples the author is aware of are the Maghribis in the 11th century and a few bands of Plains Indians in the Americas, such as the Apache and Comanche. The current Web3 inspired enthusiasts have not yet succeeded in their vision. An authentic for-profit DAO will only be proven successful once a potato makes its way from a farm to a city while relying on the DAO’s smart contracts. That DAO will be particularly successful if all the parties involved are not even aware of the technology that underlies the business transaction—similar to how people currently use Google Maps to help them choose restaurants, while they are unaware of Google’s algorithms aggregating the decentralized information from its users to make helpful recommendations.

The goal of building a DAO is as radical as any technological revolution humanity has experienced. To be thoroughly successful in this task requires decentralizing all of society, because inasmuch as a DAO relies on some other centralized institution, that becomes a bottleneck which concentrates control over the DAO, making it de facto controlled by some centralized decision maker. The degree to which any component can be decentralized is limited by how decentralized its environment is. Therefore, before the first true DAO is born, all of our government, all the businesses the DAO relies on, all of our civic and social institutions need to be revitalized to adapt to these new technological powers. Otherwise, at the very least, decentralized analogs of all these institutions must be created, to support this radical new type of democracy.

This overhaul is limited by our imaginations. We live in societies that have been dominated by centralized institutions, arguably for all of recorded history. Our understanding of decentralization derives largely from our experience with representative democracies, whose decentralization is limited to periodic votes for abdicating personal power to delegates in the government. DAOs are fundamentally different. A DAO is profoundly decentralized, since all members are capable of exerting direct control on the future of the group, via P2P technology, yet no member can assume unilateral power over any other member.

To envision the type of decentralized societies that are emerging, we can turn to history. Until the industrial revolution, the primary narrative in the story of humanity was the conflict between centralized and decentralized societies. Sedentary agriculture-based civilization versus herding nomads. Different inventions through the ages favored different sides in this conflict. The invention of the stirrup favored decentralized nomads, which led to Genghis Khan’s army razing much of the centralized world. The invention of the steam engine favored centralized societies, leading to the near-complete destruction of most nomadic cultures, due to the effects of statically-located factories producing great quantities of new inventions that favored sedentary economies, such as barbed wire.

Today, however, the inventions of the internet and personal computing enable peer-to-peer technology, which favors decentralized organization. New nomadic cultures are forming, as business can be done between individuals across national lines through virtual travel, enabled by video conferencing and distributed databases.

How can we use these new technologies to architect new types of organization to match our new powers?

1.1 Ideal DAO qualities

How does a decentralized institution emerge? How is a DAO built? What primary qualities must it have? The ideal qualities of a DAO are that it is open to pseudonymous, international members who democratically control transparent business transactions with open-source, secure governing protocols, using reputation as the measure of governmental power. Such a DAO is called a primary DAO. In the context of DAO building, let us carefully explain and justify all these terms:

1. Openness

2. Pseudonymity

3. Transparency

4. Open Source

5. Security

6. Weighted Democracy

7. Reputation Incentive

Before defining these terms, it is crucial to recognize they are ideals. As such they are never expressed with perfect purity in real world organizations. Actual DAOs exist on a spectrum of these qualities.

A DAO being open means its rules for accepting new membership is unrestrictive—everyone in the world has equal access to join, an equal opportunity to gain power, and an equal freedom to leave (while taking much of their personally accumulated value with them). It is preferable that a DAO adopt these properties of openness for two primary reasons.

First, an open network encourages greater growth, and the network effect shows a decentralized group grows in power faster than a centralized organization as its membership increases. To see this, notice how members don’t merely have connections, they have individual connections. Connections grow quadratically with membership. A group of members also has an exponential number of potential subgroups. Each subgroup of size has different role assignments. Etc. As a group grows, there is more talent and more knowledge with quadratically more connections and exponentially more arrangements to foster more powerful collaboration. An open DAO leverages the available energy of the population more effectively than a closed DAO. This network effect is a major reason that decentralized organizations can be superior to centralized organization, because a rigid hierarchy is limited to a single power structure for organizing its members to achieve a task.

The second major reason openness is ideal is that it serves the social good. It is a matter of basic justice that all people in a society are given equal opportunity to participate in all of its institutions. People prefer not to participate in a group that does not serve their values, especially one that limits their opportunities to gain power in the group. More importantly, they should not be forced to participate.

However, openness is a major security risk that needs to be continually addressed. Equal opportunity to participate is essential, but the types of participation that are beneficial to the group are naturally limited. Members who behave poorly must lose some of their power in the group, lest the group be destroyed by selfish behavior which virally spreads until the group becomes completely disorganized. Corruption must be limited or it will multiply until it destroys the group.[1] Therefore, to maintain openness, a DAO needs strong, automated, executive governance.

Pseudonymity means a member may participate with one or more fabricated identities[2]. An example is when you invent a fake username on an internet message board. It is preferable that a DAO allow members to join pseudonymously for three major reasons.

First, privacy is essential for protecting the individual. Since all transactions must be openly monitored by anyone in the decentralized network, every behavior in the DAO is recorded eternally and broadcast globally. In addition to the fear of social censure decades after any particular behavior, keeping a record of a citizen’s minute behaviors is a powerful tool which encourages governmental repression of its citizens at all levels. Pseudonymity is the closest one can achieve to anonymity on a transparent platform that remembers transactions and gives its members power and rewards.

Second, this protection of individuals’ privacy encourages more members to join. Again, the network effect gives larger groups more than a quadratic advantage in the many sub-dimensions of power, capital, and knowledge.

Finally, pseudonymity encourages a culture of forgiveness. Mistakes are inevitable. Forgiveness is essential to promote the network effect. Regardless of the intention behind the mistake, if it is possible to forgive members without eroding group cohesion, a culture supporting redemption should be promoted. Though it should be recognized that, unfortunately, pseudonymity makes apologies unnecessary, since they can simply quit and start fresh with a new identity. Conscious of this fact, a culture of redemption can still be encouraged if the DAO sets up protocols giving greater power to someone who has atoned for a mistake than to new members.

However, pseudonymity is a major security threat in an open DAO as it opens the group to sock puppet attacks, which we discuss below.

Transparency means the functions of the DAO are publicly observable. In particular, the types of technology used, the specifications for the design of the technology, the membership, the actual rate and quantity of computations or transactions, the protocols for acceptable transactions, protocols for policing transactions, the protocols for changing protocols, and even the culture of decision making, can all be made more or less transparent in any network. Inasmuch as knowledge is limited to certain individuals, when transparency is limited in any way, power becomes centralized among the subpopulation of the DAO which has the knowledge. Thus transparency is correlated with openness and power decentralization in DAOs. However, transparency is a major threat to members’ privacy, which is ameliorated when the DAO supports pseudonymity.

Open source means, minimally, that the computer code that runs the technology the DAO uses is publicly available knowledge. Similar to transparency, open-source protocols are generally necessary in an open DAO because inasmuch as it is decentralized, all members are more or less equal. No member has privileged information. Without a more powerful leader, everyone in the network needs to be able to monitor everyone else. Everyone needs to have access to the knowledge of the architecture of the system in order to audit its functioning. This is not strictly necessary in a weighted democratic governance system, since certain members can have greater power than others. But inasmuch as such power disparities obtain, the DAO is less decentralized.

Maximal open-source tech means the legal right to use that technology is given away freely, without claiming any royalties, to anyone else who wishes to use it, for any reason. An example is the Apache license[3], which governs a significant portion of internet technology. The Apache license allows you to adapt their free tech and improve it. Moreover, you can then claim ownership of your improvements and demand royalties. Such maximal open-source protocols are not necessary for any DAO to adopt. However, it is good practice to assume your protocols will be maximally open source when designing a DAO, because the international character of any open DAO makes jurisdictional questions impractical to decide and enforce. Protecting your IP in this environment is better handled by using the first mover advantage, combined with the network effects that make your DAO more powerful than any later imitators. This works best when additionally, a culture of proper referencing evolves to acknowledge and fairly reward improvements from the past. Such meritocracy can promote a more effective collaboration environment than one which stresses competition and secrecy.

Security is a constant concern in the design of an open-source protocol. Especially when the network is open to pseudonymous members. Byzantine behavior in a decentralized network, is defined as actions which violate the majority agreed protocols. When there is no dictator ruling your platform, and you accept asynchronous distributed transactions entering from any node, it is impossible to achieve perfect intelligence about the state of the network, since Byzantine nodes can pass false messages in the gossip network. There are several theorems in computer science that govern what is possible when designing a protocol for distributing digital token rewards in a DAO. A famous example is the 66% non-Byzantine limit for the pBFT algorithm. In general, no decentralized system can survive forever in the face of 51% Byzantine actors. Therefore some restrictions to openness are necessary.

Another major security risk to a decentralized platform is a sock puppet attack. Sock puppets are multiple pseudonymous accounts that a single member creates and controls with separate passwords to hold digital tokens. The purpose of sock puppet accounts is to trick the network into believing the different pseudonymous identities represent multiple people. This eliminates any chance that a DAO without KYC protocols can achieve honest governance under simple one-person-one-vote democracy. Since anyone on the planet has equal opportunity to participate under a fabricated identity, a single actor can create countless sock puppet accounts to overwhelm the voices of honest members. Therefore, any DAO work model or governance design must account for this eventuality. The solution to fighting sock puppet attacks, is a weighted democracy which assign rewards and power based on carefully audited measures of positive contributions to the group.

A weighted democracy is a governmental structure where the power to decide the protocols for the DAO is determined by vote (democracy), but the power of each person’s vote may be different (weighted). This is necessary in an open pseudonymous group, because it eliminates the threat of sock puppet attacks: 100 sock puppet accounts voting with 1 weight each have the same power as a single account voting with 100 weight, since both situations have the same total.

How is this weight of power determined? In most of the original functioning DAOs, power is dictated by ownership of the currency token. In that case plutocracy is the de facto governmental structure. Little reflection is needed before most new DAO architects reject this design. Instead the common solution is to build their DAO on reputation.

Reputation is a personal judgement based on your past actions. Business relies on your counterparty’s reputation to predict how they will act during a transaction, to give you the confidence to enter a bargain. The proper attitude for a healthy market environment is to seek to improve and protect your reputation for the long term, not to simply acquire as much money as possible in a single business deal. A secure and reliable system that accounts for meaningful reputation transforms such zero-sum competitive behavior concerned with immediate profits into an environment which motivates future-oriented, sustainable cooperation. When a single game turns into a repeated game, the incentives are transformed. In a system with repeated business, reputation is actually a positive sum quality, since it can be created from nowhere. Whenever two parties behave well and collaborate productively, perhaps sacrificing their own short-term gain on some aspects of the deal, they produce valuable reputation that signals further positive interactions in the future.[4]

How can we foster a culture which respects and values reputation more than money when your DAO allows pseudonymous members to join or leave at will? Properly designing and programming a robust mechanism that is secure against the infinite strategies for gaming any algorithmic reputation system is not a simple task. The remainder of this chapter is devoted to explaining how to capturing the meaning of genuine reputation with digital REP tokens, analyzing the system’s security, and specifying precisely the economic value of a REP token, and detailing important applications.

[1] Corruption is defined abstractly in a system as the result of a minority profiting at the greater expense of the majority. Corruption is a type of friction that is inevitable in any system, because the will to profit is essential and the accounting to determine whether a minority’s profit is at the greater expense of the majority is generally not a tractable problem before the fact.

[2] Pseudonym technically means false identity, which has a negative connotation. It would be preferable to have a more neutral term meaning fabricated name, such as technonym, synthenym, artinomen, or fabrinomen, since the identities we are discussing are not necessarily inherently false. However, the term pseudonym is firmly established in the field.

[3] https://www.apache.org/licenses/ Retrieved 18/2/2023.

[4] An elaborated argument for the necessity of reputation in business is given in Chapters 4 and 6 in [??Craig Calcaterra and Wulf Kaal, Decentralization, De Gruyter, 2021]. We rely on game theory [?? George J. Mailath and Larry Samuelson, Repeated Games and Reputations: Long-Run Relationships, Oxford University Press, 2006.] and history [??Avner Greif].

Fundamental Considerations[edit | edit source]

- Individuals are creative, and have goals and needs

- Individuals can choose to coordinate their actions

- This can be considered a social phenomenon

- These actions and reactions aggregate into group behavior

- Group behaviors have effects

- Individuals within the group

- The group considered as a whole

- Outside the group

We desire to build a system with the following properties:

- The system accrues benefit to its users, both internal and public

- The behavior of the system can be steered by the collective will of participants

We call such a system a Self-Governing DAO (Decentralized Autonomous Organization).